A series of short

articles on the Bhagavad Gita for people living and working in our volatile,

uncertain, complex and ambiguous times filled with stress and fear. This

scripture born in a battlefield teaches us how to face our challenges, live our

life fully, achieve excellence in whatever we do and find happiness, peace and

contentment.

[Continued from

the previous post.]

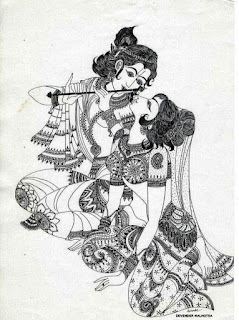

The name given to

the first chapter of the Gita is Arjuna Vishada Yoga – the Yoga of Arjuna’s Vishada.

The word vishada is translated variously as melancholy, sorrow, grief, depression,

despondency, sadness, misery and so on.

We just saw in the

last article how Arjuna surrendered to melancholy, dropped his bow and arrows

and collapsed into his chariot telling Krishna he will not fight, he finds no

point in fighting and killing, no point in winning the kingdom, no point in

pleasures or even in life itself. Kim no rajyena govinda, kim bhogair jeevitena

vaa, he asks: “What good is the kingdom, Krishna, and what good are pleasures

or life itself?”

All over the world

today there is a lot of discussion about depression which is fast spreading and

assuming the form of a wild fire that can consume everything. I was part of the

faculty team giving an intensive training programme for doctors at XLRI School

of Business and Human Resources and we were having a pre-programme dinner when

the topic of depression came up. Several professors felt depression is fast

becoming the most dangerous problem the world is facing today with a large

number of lives claimed every day. This was of course in the days before the

covid-19 pandemic.

Bright young

people seem to be particularly susceptible to depression. In his bestselling

book The Happiness Advantage: The Seven Principles of Positive Psychology,

Shawn Achor speaks about depression in Harvard University where happiness was

the subject of his research for several years. Achor says “despite all its

magnificent facilities, a wonderful faculty, and a student body made up of some

of America’s (and the world’s) best and brightest, it is home to many

chronically unhappy young men and women. In 2004, for instance, a Harvard Crimson poll found that as

many as 4 in 5 Harvard students suffer from depression at least once during the

school year, and nearly half of all students suffer from depression so

debilitating they can’t function.” Shawn Achor then goes on to say that “This

unhappiness epidemic is not unique to Harvard. A Conference Board survey

released in January of 2010 found that only 45 percent of workers surveyed were

happy at their jobs, the lowest in 22 years of polling. Depression rates today

are ten times higher than they were in 1960. Every year the age threshold of

unhappiness sinks lower, not just at universities but across the nation. Fifty

years ago, the mean onset age of depression was 29.5 years old. Today, it is

almost exactly half that: 14.5 years old.”

Speaking about depression, the Himalayan monk Om Swami says in his book When All Is Not Well: Depression and Sadness:

“Depression isn’t just sadness. It is emptiness, it is misery. It is pain and

nothingness at once. When you are truly depressed, you lack the ability or will

to cheer yourself up. No one just ‘has depression’. You suffer from it.”

Continuing, Om Swami explains what depression feels like. “You will wake

at 5, 6, maybe 7 a.m., feeling as though you had only just fallen asleep... If

you don’t have to be somewhere, you could lie in bed for another three hours;

too tired, too miserable and pathetic to crawl out of your bed. Or maybe you will

sleep until 1 p.m., because it’s so much easier to sleep through most of the

day than actually live it, and you’re so unbelievably tired anyway. You will

push through the day, knowing that every hour will be a struggle and not

knowing how you will feel tomorrow. People will ask what is wrong, and you will

simply smile and say, ‘Nothing, I’m just tired.’ ...You will spend your days

not only lost in the haze of depression, but your mind will be so consumed with

these thoughts of escaping and self-destruction that you think you could

explode…”

But the important

question is why so many people are feeling depressed today. Why is depression

spreading across the world like a deadly epidemic today?

The reasons are

not too difficult to find. For one thing, our life has become too fast. We are

obsessed with speed – in real life as well as in virtual life. We have become

intolerant of slowness. And stillness? Of course, we have grown strangers to

it. We have forgotten that all that is beautiful in life comes from stillness.

Creativity comes from stillness. Intuition comes from stillness. Art and music

come from stillness. The essence of dance is not movement but the stillness

that is its substratum, from which arises and into which it goes back. All

inventions and discoveries are made in moments of stillness. Intuition comes

from stillness, insights come from stillness, healing comes from stillness. Medical

professionals have long recognized that silence plays an important part in

healing. For instance, the experience of even a little real silence can produce

physiological changes that neutralize the effects of stress.“When you are

still, you find that your perception of life is at its purest,” says Ron

Rothbun in his book The Way Is Within.

We are all

familiar with the story of Archimedes who ran through the streets of Athens

shouting eureka, eureka. The Athenian ruler had given him an assignment.

Someone had gifted the ruler a crown and he wanted to find out if the crown was

of pure gold or some alloy had been mixed with the gold. The specific gravity

of gold was known then, but no one knew how to measure the mass of an irregular

object like the crown. Archimedes was the best scientist of the day and he

struggled for weeks to find a solution to the problem. If only there was a way

to measure the mass of the crown! Then you could decide whether the crown was

pure gold or not.

Eventually

Archimedes gave up his struggles admitting defeat and sank into a tub for a

relaxed bath. It was then, in that moment when there were not struggles in his

mind and the mind had become still with his acceptance of defeat, that he

noticed water spilling over from the tub as his body sank into the tub. That

very instant insight was born, a great discovery happened: the mass of water

that spilled out was equal to the mass of his body that had submerged in the

water. The quantity of water that flows out when a substance is immersed in a

vessel full of water is equal to the mass of the substance.

In that still

moment, his problem had been solved and climbing out of the tub he ran through the

streets of Athens shouting that word that has now become part of every language

in the world: eureka, eureka!

We all have had

the experience of something, a name, we had forgotten coming back to us the

moment we give up the struggles and the mind becomes still.

All science and

all technology is the product of still moments. All that is precious to

humanity are products of inner stillness, of the mind is that is empty of

restless thoughts. The saying that the empty mind is the devil’s workshop is

completely wrong. The empty mind is God’s workshop!

Indian culture

says the universe is born of God’s empty mind. The Taittiriya Upanishad says,

“Sa tapo’tapyata. Sa tapas taptvaa idam sarvam asrjata. Yadidam kincha.” “He

did tapas. Having done tapas, he created all this. He created all that exists.”

It is from the mind of God that has become empty because of tapas that the

universe comes into being.

There is story

told about the world famous painter Raphael and an unknown woodcutter. One

morning as the woodcutter was going to the forest to cut wood, he saw Raphael

sitting by a lake, lazily picking up pebbles and dropping them into the lake.

The woodcutter shook his head in disapproval – what a waste of time! – and went

on his way. As the woodcutter was returning home with his load of firewood, he

saw Raphael still sitting there picking up pebbles and throwing them into the

lake! What an idiot, he thought! I have done a whole day’s work and the moron

is still sitting there and throwing pebbles into the lake!

We know today that

such a woodcutter existed because of Raphael, one of the greatest painters the

world has known.

In the ancient

Indian tradition, in fact all over the world, we began everything with a few

moments of silence, of mental stillness, of prayer. But today stillness, and

even slowness, is looked down upon. It is one of the greatest casualties of the

age of speed.

The virtues of

slowness are unlimited, says Carl Honore in his book In praise of slowness. In his book Slowing Down to the Speed of Life, Richard Carlson says more or

less the same thing. And it is that slowness that we have rejected in favour of

speed! Faster, faster, ever faster, says our culture!

Slowing down and

experiencing stillness is one of our basic needs – it is as essential as

breathing. Our brains go completely haywire unless we experience slowness and

stillness on a regular basis. Which is exactly what is not happening today. And

that is taking a heavy toll on young minds today, especially gifted young

minds, leading to depression and all that depression leads to. The philosophy

aaraam hai haraam has to go. Laziness is bad, sluggishness is bad, sloth and

apathy are bad, but relaxation is not. It is the most healing thing most of us

know, apart from sleep. In fact sleep is a form of relaxation too. The second

highest form of relaxation, after meditation which is the highest form of

relaxation in existence.

We need to spend

more time ‘plucking daisies’, we need to spend more time climbing mountains, we

need to spend more time unfocused and in ‘purposeless’ activities, like Raphael

picking up pebbles and throwing them into the lake. We need to give our souls

time to catch up with us. That is the medicine for fighting the insane

obsession with speed that drives us away from our own calm inner centre.

A European

explorer was in the Amazon forests, exploring the flora and fauna there. He had

hired a supervisor and the supervisor had hired native people to help him in

his work. One day passed the explorer and the natives hurrying from one thing

to another, then another day and then yet another day. On the fourth day when

the explorer was ready to start he found not one native was ready. When

enquired, the supervisor gave him an incredibly beautiful reply. He told the

explorer: they are giving time for their souls to catch up with them!

We all need to

give time for our souls to catch up with us.

One of the most

beautiful Chuang Tzu stories ever says:

The prince

discovered when he returned from the top of the mountain that he had mislaid

the Priceless Pearl up on the mountain.

He sent his

generals and their armies to search for it, but they could not find it. He

employed Huang-Ti, the vehement debater, to find the Pearl, but Huang-Ti was

unable to find it. He sent his skilled gardeners and his artisans to find it,

but they too came home empty-handed.

Finally, in

despair, having tried everyone else, he sent Purposeless to the mountain, and

Purposeless found the pearl immediately.

"How odd it

is", mused the Prince, "that it was Purposeless who found it!"

We are all birds

meant to fly in the open sky. Those who have known the truth, the Upanishad

rishis for instance, call us amritasya putraah – children of the Immortal, each

one of us a divine spark. The Mundaka Upanishad tells us: yathaa sudeeptaat

paavakaad visphulingaah sahasrashah prabhavante saroopaah, tathaa aksharaad

vividhaah somya bhaavaah prajaayante tatra chaivaapi yanti: Just as sparks in

their thousands are born from a roaring fire, each of the same nature as the

fire itself, so do, dear one, beings come forth from the Imperishable One and

return to It. [Mu.Up.2.1]

No, we are not

meant to spend our lives hopping about on the ground searching for worms but to

stretch out our wings, soar up and enjoy the bliss of the boundless skies – the

boundless skies of consciousness. We are meant for the bhooma, the vast, and

not for the alpa, the small. The owl will be satisfied with the rotting body of

a mouse, but not the phoenix which will touch no food other than certain sacred

fruits and drink only from the clearest springs. The chakora lives on

moonbeams, says Indian mythology, and will touch nothing else. The way man

lives today is like the phoenix being forced to live on rotten mice and the

chakora being forced to live on the food that pigs eat.

By and large, man

has forgotten the higher. We have become flotsams with no roots in our

spiritual selves. We are living not the philosophy of the rising son as we did

in the past but the philosophy of the setting sun. Frustration and depression

are bound to be there.

O0O

As we saw, the

vishada that happened to Arjuna in the battlefield is called by different names

such as melancholy, sorrow, grief, depression, despondency, sadness, misery and

so on

But there is a different

name for it. India calls it vairagya, dispassion, and considers it sacred. Vairagya

is the first step in the journey to the east, the journey to the land where the

sun rises, the journey to the source of all light. Light as bright as the light

of a thousand suns, light before which all other lights pale.

There is mantra

that is traditionally chanted when we do arati, ritually show burning lamps

before a sacred idol. Na tatra sooryo bhaati na chandrataarakam nemaa vidyuto

bhaanti kutoyam agnih; tam eva bhaantam anubhaaati saravam tasya bhaasaa sarvam

idam vibhaati, says the mantra. “The sun does not shine there, nor the moon or

the stars. How then will this fire? That alone shines and everything else

shines after it, reflecting its light.” The journey to that source of all light

begins with what Arjuna is experiencing now and that is why India considers

vairagya sacred.

This is something

that happens only to sensitive people. Much of the time the kind of questions

Arjuna asks, the feelings Arjuna feels, come to us from a great shower of blessing

that descends upon us. It is ishwra-anugraha, the grace of God, says India.

The rishi of the

Svetashvatara Upanishad declares boldly and unhesitatingly:

vedaaham

etaṃ puruṣhaṃ mahaantam aaditya-varṇaṃ tamasaḥ parastaat;

tam eva viditvaa atimṛtyum eti naanyaḥ panthaa vidyate'yanaaya. Sv. Up. 3.8

tam eva viditvaa atimṛtyum eti naanyaḥ panthaa vidyate'yanaaya. Sv. Up. 3.8

“I

know the Great Purusha, He who is luminous like the sun and beyond darkness.

Only by knowing Him does one go beyond death. There is no other path worth

travelling!”

Vairagya

is the invitation to begin our journey on the only path worth travelling.

It is

not only Arjuna who has grace showered on him as he stands in the chariot

driven by Krishna in the middle of the two armies in Kurukshertra, but all of

us, the entire humanity. Because it is in response to this vairagya he felt

that the Bhagavad Gita was born on a shukla paksha ekadashi day, on the

eleventh day of the bright lunar fortnight in the month of Margashirsha, more

than five thousand and one hundred years ago.

A well

known story from the Mahabharata says that both Arjuna and Duryodhana went to

meet Krishna seeking his help before the war began. Duryodhana was the first to

enter Krishna’s bed chamber and he went and took a seat by the head of the bed.

A few moments later Arjuna entered the chamber and he too could have gone and taken

a seat at the head of the bed as Duryodhana had done. Instead, he went and

stood at Krishna’s feet. When Krishna opened his eyes a few moments later it

was naturally Arjuna who was standing at the foot of the bed that he saw first.

As we all know, it was on him that Krishna’s grace fell in the form of his

presence with him during the war and as his driver.

Krishna is grace.

The greatest possible grace! With Krishna on your side, the impossible becomes

possible. With Krishna on your side miracles happen. Mookam karoti vaachaalam

pangum landhayate girim, yat-kripaa tam aham vande parama-ananda-maadhavam,

says one of the shlokas traditionally chanted before the study of the Gita: “I

bow down to Krishna, who is supreme bliss itself, with whose grace the

speechless become eloquent and the lame crosses over mountains.”

The choice that

Arjuna made in Krishna’s bedchamber, rejecting the Narayani Sena, rejecting the

power of a mighty army and choosing just Krishna, Krishna’s grace, it is that

choice that is now showering on him in the form of the Bhagavad Gita. All we

have to do is to make that choice, everything else happens by itself. That is

why Krishna concludes his teachings in the Gita by saying:

sarvadharmaan parityajya maam ekam sharanam vraja; aham twaa

sarvapaapebhyo mokshayishyaami maa shuchah BG 18.66

“Abandoning all dharmas, take refuge in me alone; I will

liberate you from all sins. Have no grief.”

Duryodhana missed

Krishna’s grace throughout his life. After the war was over, Gandhari curses

Krishna saying he could have and should have helped her son but did not. But

grace can shower on you only when you are open to it. If a pot remains upside

down when the sky showers rains, not a drop will go inside even if an entire

season passes. In fact, the only thing you need to deserve grace is openness to

it, receptivity to it, which is what Duryodhana did not have. There were a thousand occasions in his life when

he could have taken refuge in Krishna, but rejects every single one of them.

There is a famous

Indian story about a beggar who was crossing a bridge, walking with a stick in

hand. The story says that Goddess Parvati takes pity on the poor beggar and

requests Shiva to bless him with wealth. Shiva says there is no point because

even if he gives wealth to him, he will not get it because he is not open to his

blessing. But the heart of the goddess is the heart of a mother and she insists

that the man be given wealth. Shiva agrees and a treasure chest appears on the

bridge. The moment the chest appears on the bridge, the beggar has a thought:

“I am young now and I can see well, but what will happen to me when I grow old

and lose my eyesight? I must practice walking blind right from now.” With that thought, he closes he eyes and walking

with the help of the stick crosses the rest of the bridge, missing the treasure

completely!

Throughout his

life Duryodhana behaved like that beggar.

Whereas Arjuna

chose Krishna lifetimes ago. The Mahabharata tells us they have been friends

across lifetimes, meditating in the Himalayas together.

There is a mantra

in the Mundaka Upanishad that my teacher Swami Dayananda Saraswati was very

fond of. During the years when I was in the Sandeepany Gurukula and learning

timeless Indian wisdom from him, he must have quoted this mantra hundreds of

times.

pareekshya lokaan

karmachitaan braahmano nirvedam aayaan naastyakrtah krtena tadvijnanartham sa

gurum evabhigacched samitpaanih shrotriyam brahmanishtham. Mu.Up.1.2.12

“Having

examined all in the world that is gained through actions, after attaining

nirveda and realizing that the uncreated cannot be achieved through actions,

let [him who has thus become] a brahmana, approach with samit in hand a guru

who is learned [in the traditional spiritual lore] and rooted in the Brahman.”

The

soul of the entire Indian spiritual culture could be found in that one mantra.

Before approaching the guru and being qualified for his grace, we must

developed nirveda towards all that can be attained through our own power,

through our actions. Nirveda means vairagya – what Arjuna is experiencing at

the moment. It is when this vairagya is born in your heart that you become a

brahmana – one whose entire focus is on

attaining the Brahman, one whose concentration now is only on attaining

the spiritual goal. And then he should go to his guru with samit in hand. Samit

is kindling used in sacrificial fire. Carrying that to your guru is the symbol

of your joyful willingness to serve the master.

Duryodhana is

still far from the nirveda the Upanishad talks about. He is not willing to

surrender to Krishna and therefore is not ready for the grace. He has not yet

developed what makes you a brahmana – the all consuming urge to abandon

everything else and walk the path of shreyas to reach the land of the ultimate

good, the land of light, having reached which you never return – yad gatvaa na

nivartante. He is still very much with the loka of wealth, power, position,

sensual pleasures and so on.

Arjuna has developed

that urge and he is ready. That is why he is asking, “What good is the kingdom,

Krishna, and what good are pleasures or life itself?” The vishada he is

experiencing at the moment is the clear sign of that.

All vishadas, depressions, are not bad, some are good. Some can take you to the higher. They

come to you from divine grace. With them begins our journey to the east, the

greatest journey we will ever make.

O0O